Grande Sonnerie [Def]: a watch that strikes the hours and quarters automatically.

The Professional Dictionary of Horology is clear about the function of a Grande Sonnerie. But let’s understand what it means by “automatically.” Here it does not refer to an automatic movement, but rather that, without outside help, the watch will strike, on its own, in passing, every hour, and repeat the hours and indicate the quarters at each quarter. (Note that in Petite Sonnerie mode, it will strike the hours on the hour and only the quarter on the quarter, similarly to a grandfather clock.)

When François-Paul Journe embarked on what he later called the “climbing of Mount Everest,” there was no modern Grande Sonnerie in the market. Most of the offerings were old pocketwatch movements mounted in wristwatches. His specifications were set in stone from the get-go. Not only would his creation follow the exact definition of a Grande Sonnerie, but it had to have a long power reserve and be able to be used by a 10-year-old child.

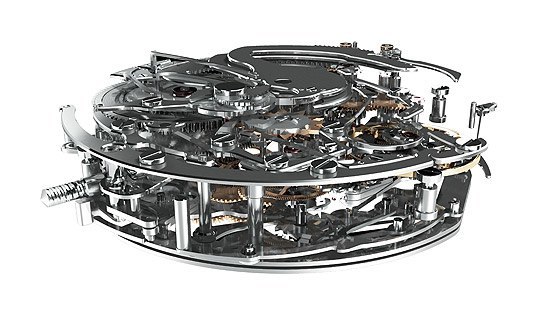

A mere six years and 10 patents later(!), the F.P. Journe Grande Sonnerie Souveraine was born, and won the Golden Hand at the Grand Prix d’Horlogerie of Geneva in 2006. What makes this watch so revered and complicated?

Friction and power issues (as in all mechanical watches) are exacerbated in the Grande Sonnerie. Consider friction: the Grand Sonnerie chimes 96 times per day; the hammers strike 912 times per day or 332,880 times per year. Which brings another problem to the plate: wear and tear! Just imagine hitting a table with a little hammer that many times. It would destroy the table.

As for the issue of power, the “easiest” way to circumvent this extraordinary thirst of energy would be to add a few mainsprings or to have a short power reserve. Journe did none of that. He created (and patented) a unique mainspring mechanism that feeds the timekeeping functions on one side and the chiming ones — independently — on the other. Thus, timekeeping has a power reserve of five days. When it is in Grande Sonnerie mode, the Sonnerie will work for 24 hours, after which a (patented) system blocks the chiming mechanism, leaving still 24 hours of timekeeping. If the watch does not chime, it is time to wind it.

The other issue is the protracted fragility of Sonneries. The F.P. Journe Sonnerie Souveraine features patented security systems that keep the watch from striking when the winding crown is pulled out, and that ensure that the winding crown may not be pulled out during striking. It is somewhat similar to a perpetual calendar that would prevent you from setting between certain hours (as the gears are engaged). This results in total security, and ensures for the first time that the mechanism cannot be damaged by incorrect manipulation — therefore making it the only striking watch that is completely safe to use.

The Grande Sonnerie –like every chiming watch from Journe (i.e., the Minute Repeater) is in steel. Steel has a crystalline formation, as opposed to platinum and titanium, which are made from an aggregate of powder. Sound has two components — volume and quality — and steel offered the best compromise.

Sound and vision?

Why do Grande Sonneries (and minute repeaters) delight the watch collector so much? One clear answer is that their level of complication is unmatched. It seems a bold concept — hearing the time versus seeing it — but this is not actually new. Actually, time was heard rather than seen for centuries. When time began to be communicated in the 14th and 15th centuries in Europe (Northern Italy, France and Germany, mostly), the clocks in churches did not have dials. After all, who would see them? Certainly not the farmers, who could be miles away. So, monks or priests hit on bells to indicate time to those far away.

Proof? When we say 4 o’clock, we refer to “4 of the clock,” which, in the late 14th century, meant bells (clock comes from the Old French cloke; Modern French is cloche for “bell”). Thus, 4 o’clock means literally “4 of the bell.” More proof? The origin of the word “noon” comes from the nona prayers. Nona used to refer to the ninth hour of sunlight, but in the mid-12th century, church prayers shifted from ninth hour to sixth hour, or roughly midday. Once again we referred to sound – hearing the nona prayers, one knew it was 12 noon.

The Grande Sonnerie is a testament of F.P. Journe’s vision: do one complication per movement but do it as well as you can and do it while limiting the number of parts (so as not to create more friction or problems). This movement has “only” 408 parts and an overall diameter of 35.8 mm. To quote Antoine de St Exupéry from “Night Flight”: “A designer knows he has achieved perfection not when there is nothing left to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.”

To view a video of the movement: http://www.F.P.journe.com/eu/collections-fr-sv-gds-1.html?v=modele

Read also our previous Insider’s Looks:

Power or Precision? An Insider’s Look at F.P. Journe – Part 1

Who Needs Constant Force? An Insider’s Look at F.P. Journe – Part 2

Is Your Wristwatch a “Wrist” Watch? An Insider’s Look at F.P.Journe – Part 3

How to Make a Perfect Watch: An Insider’s Look at F.P. Journe, Part 4

For more information, www.fpjourne.com

Or visit or contact one of our F.P. Journe Boutiques:

Bal Harbour shops Mall at +1 305 993 4747; miami@fpjourne.com

Los Angeles: +1 310 294 8585; losangeles@fpjourne.com

New York: +1 212 644 5918; ny@fpjourne.com