It has been nearly 20 years since Ulysse Nardin introduced the world’s first timepiece using silicon components with the original Freak in 2001. That groundbreaking moment was the proverbial starting gun for a shift in how the watch industry approached movement production. It’s also raised questions on every side of the industry, from the enthusiast level to the executive perspective, about the soul of watchmaking and how using state-of-the-art technologies and materials impacts the craftsmanship and artistry that have been intertwined with horology since Abraham-Louis Breguet walked the earth.

For many collectors, the debate falls on whether or not the added value these man-made materials bring to end consumers outweigh the romantic and emotional ideals behind watch collecting. Does an old-fashioned product like a mechanical wristwatch require an old-fashioned solution? How important is performance-oriented innovation actually to watch collectors?

The Benefit of Silicon

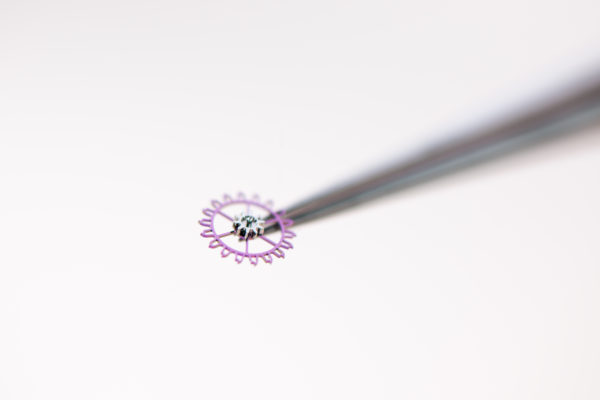

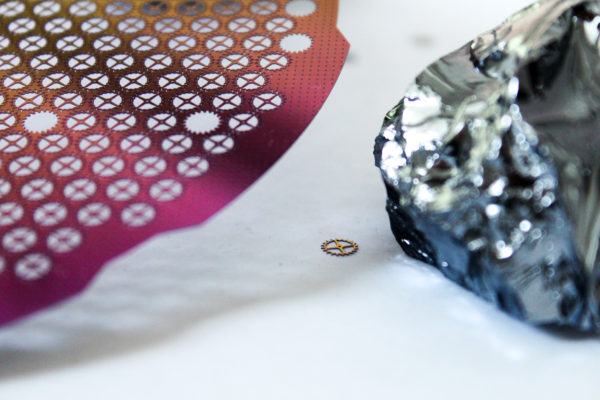

Silicon, also referred to throughout the industry as silicium, is a material borrowed from the worlds of semiconductors and microprocessors and its benefit in watchmaking is simple enough to grasp without going into the complicated minutiae of horological engineering. Its best known attribute is the fact that silicon is completely antimagnetic and corrosion resistant. It offers enhanced stability to temperature variations and does not require any lubrication. Thanks to its lightness, it allows for greater efficiency in the transition of energy and a higher level of timekeeping accuracy due to its increased rate stability. It is elastic to the point of 130 – 170 GPa (gigapascals) and can be etched with precision at both micro-metric and sub-micro-metric levels. In fact, silicon is so elastic that it can be shaped into any desired form during the DRIE (deep reactive-ion etching) process and mass-produced.

The usage of silicon as a micro-mechanical component started in the 1970s with the development of Micro-Electro-Mechanicals Systems (MEMS) for computer systems. Today, MEMS manufacturing can be found in all sorts of industries ranging from inkjet printers and scanners, to video games and cameras. In watchmaking, its benefit is not limited to what it offers from a purely functional standpoint, it’s also rather simple to prototype, making creating new concepts and applications a simpler endeavor compared to working with metals or other alloys. Additionally, it offers more precise manufacturing with less error potential during the testing and production stages.

Dr. Ludwig Oechslin, who was a key figure in the development of the first Freak, recently described to WatchTime the story of how the first silicon escapement was conceptualized and brought to the public in 2001.

“At that time, I had developed a new escapement and delivered it to Ulysse Nardin. The escapement consisted of two wheels (instead of just one) and therefore double the mass had to be moved. With the Dual Direct escapement from Ulysse Nardin, the impulse is directly symmetrical on the balance axle. It is, therefore, a regular impulse without the friction loss of an anchor. This can lead to higher precision. With the conventionally used materials, the potential advantage of the design compared to a conventional escapement was only an improvement of about 10 percent. A real innovation is an improvement of 30 to 40 percent. The moment of inertia and therefore the weight of the escapement wheels had to be reduced. The first unsatisfactory attempt was with an aluminum/ nickel alloy. Pierre Gygax, together with Technickum Le Locle, came up with the idea of using silicon.”

Since then, Ulysse Nardin has remained a leader in the development of silicon technology and has often taken a more inventive approach than others to its application. New Freak Concept timepieces are consistently announced with clear intention of their future application in production models. The Freak has remained at the center of silicon innovation and has become one of the most recognizable icons of contemporary horology because of it.

“The microfabrication of silicon components is a key contribution to modern watchmaking,” affirms Stéphane von Gunten, the current Research and Innovation Director at Ulysse Nardin. “I was involved in sensor and actuator projects while working in a Swiss institute for microtechnologies, just after 2000. At that time I could not expect how important the value of the silicon would be for the watchmaking industry.”

At the Swatch Group, the usage of silicon has already paid clear dividends for consumers. For example, Omega recently extended its warranty to an industry-leading five years, thanks, in part, to the reliability that silicon provides. While other details such as the METAS chronometer certification and the co-axial movement ensure reliability to a certain degree, there’s no question that the introduction of wear-resistant silicon has played a big part in Omega’s confidence to offer a warranty that lasts half a decade.

Other than its clear performance benefits, it’s worth mentioning that while wearing a watch that uses silicon or other high-tech materials on the wrist, it feels like any other mechanical timepiece. If a non-enthusiast picked up a watch that used silicon components after decades of wearing more traditional mechanical timepieces, they wouldn’t be able to tell the difference other than the few clear benefits like longer service intervals and not having to avoid magnetism, but there’s a good chance they wouldn’t be aware of that difference without being told anyway. It’s also worth mentioning that the presence of silicon does not take away from the artistry involved in high-end movement finishing either.

The Case Against Silicon

It’s impossible to refute the fact that silicon components further the science of chronometry, but for many collectors and members of the horological cognoscenti, silicon also raises the question of the purposed “soul” of watchmaking. As dynamic as silicon as a material is, many wonder how something grown in a lab or a “cleanroom” can operate within the emotional world of watch collecting, which is still rooted in old-world sensibilities for many. For collectors that watched the luxury watch industry barely emerge from the Quartz Crisis, introducing another high-tech material borrowed from the alien world of computers is tough to swallow. Given the brittle nature of silicon, it also makes the movement impossible for a local watchmaker, someone that can be ingrained within the surrounding watch community for decades, to operate on and is a stark departure from the classic ideal of someone at a workbench with a loupe in their eye to the surgical world of 21st-century tech.

When WatchTime editor Mark Bernardo had the opportunity to sit with the late George Daniels in 2010, the watchmaker that many consider to be the greatest of the 20th century (himself an escapement pioneer) stated his disapproval in regards to the proliferation of silicon and other technologies in watchmaking.

“I don’t believe they’re necessary, no. There is no evidence that they are. Clocks and watches have been made of brass and steel for a thousand years, and they’re still running perfectly. We don’t need these things. I don’t accept these materials as being the least bit useful in haute horlogerie.”

This view is backed by a number of key contemporary figures in the worlds of movement production. Sébastien Chaulmontet, the former Head of Innovation at Arnold & Son and Angelus and current Head of Innovation and Marketing at Sellita, believes that silicon has definite benefit to offer collectors through its lightness and elasticity, but that its potential has been overstated.

“The widespread adoption of silicon is not something which should be an aim for itself,” Chaulmontet says. “It only makes sense for certain uses. Two main reasons against the widespread use of silicon are its intrinsic fragility and the fact that it is not repairable by a watchmaker as it needs specialists. Therefore, silicon brings an obsolescence factor into the mechanical watch which is fundamentally against its core attributes of longevity, reparability in the long run, etc.”

Planned obsolescence is a frightening term that recalls the disposable nature of tech products like smartphones, tablets, and laptops. It’s also the complete opposite of why esoteric pursuits like luxury watchmaking still exist. It’s easy to recall the Bulova Accutron that featured groundbreaking technology when it was introduced in 1960, but is nearly impossible to repair in the 21st century. If the industry is to move away from silicon to whatever the next big revolution is, then what is to come of all the watches ticking away with silicon parts? It isn’t something you can reproduce at home, that’s for sure.

“Mechanical watchmaking is a little bit like classical music,” Chaulmontet says. “There are rules set to stay that are not open to all kinds of innovation – no electric guitars for instance in this analogy. Only the innovation that does not question its core values is acceptable. This is not a bad thing as its only raison d’être nowadays is to be a form of mechanical art. From a pure technological standpoint, it is dead for decades now. It survived because of its beauty and not because of fundamental innovation. Silicon crosses the red line by questioning reparability and also because of its production means. Personally, I think that we will see in the future two kinds of mechanical watchmaking. The first type will be highly innovative and cross frontiers to other fields like electronics and the other one will be highly traditional. The latter will probably not use silicon as it does not reflect the values of traditional watchmaking.”

As most watch enthusiasts are aware, Sellita is a leading manufacturer of movements for the watch industry. It offers robust calibers that can be found in brands of all sorts from small-scale microbrands to companies with huge production capabilities like Oris and Bell & Ross. Chaulmontet says that because of Sellita’s commitment to providing the watch industry with a huge number of calibers, they “must be rock solid and serviceable around the world by any kind of trained watchmaker.” Due to those factors and silicon’s overall fragility, it is unlikely we’ll see silicon used in Sellita’s production calibers anytime soon.

On the other side of the spectrum, Dr. Oechslin remains steadfast in his belief of the value silicon offers watchmaking as a whole. “The possibility of producing something more precise always makes sense with mechanical watches and is therefore not ‘soulless,’” he says. “The value of a component today lies more in the construction and if this is well considered then it is valuable. In most mechanical watches today, the components are interchangeable anyway. The value therefore clearly lies in the good construction.”

Who is Doing What?

Tracking the usage of silicon in today’s watch industry is a bit complex. Ulysse Nardin presented the Freak in 2001 and soon helped set up a manufacturing partner named Sigatec for further R&D work in both watchmaking and bio-medical fields. The brand, which is now owned by the Kering Group, has continued its exploration of silicon and recently released a concept watch called the Freak NeXt that features a three-dimensional flying oscillator constructed of four silicon wheels stacked on top of one another. Inside each of these four wheels are eight silicon blades that offer enhanced elasticity and a higher vibrational frequency. All of these wheels combine to create a “virtual pivot point” that effectively disposes of the need for a traditional balance construction, completely eliminates any friction on the bearings (no jewels necessary), and increases the efficiency of the movement’s energy consumption. The 32 micro-blades that make up the new flying oscillator measure just 16 micrometers in width and are connected to one another without any contact with the mainplate.

Around the same time as Ulysse Nardin’s initial efforts were coming to fruition, an investment consortium was formed by Rolex, Patek Philippe, and the Swatch Group to back research by the Swiss Center for Electronics and Microtechnology (CSEM) into the benefits of monocrystalline silicon. These three titans of contemporary watchmaking soon became industry leaders in silicon’s watchmaking application because of this.

Patek Philippe was the first of the consortium to make widespread use of the material thanks, in part, to its Advanced Research division. In 2005, the Silinvar escape wheel was announced that required no lubrication. It was followed in 2006 by the concentrically breathing at Spiromax balance spring with a terminal curve for improved isochronism. In 2008, the Pulsomax escapement in its entirety was released inside the Annual Calendar Ref. 5450 for more efficient power transmission. Finally, in 2011, the GyromaxSi balance appeared within the Perpetual Calendar Ref. 5550P. The construction of this balance consisted of two diagonally opposed circular sectors crafted from Silinvar and 24k gold. The chassis was etched out of silicon wafers with the DRIE process and converted into a Silinvar component by way of oxidation. The centrifugal masses were gold inlays integrated into the chassis with a technique patented by Patek Philippe. The GyromaxSi balance also featured four small slotted poising weights that could be precision-adjusted according to the Gyromax principle (variable moment of inertia).

The Gyromax adjustment concept was originally developed by Patek Philippe in the 1940s and received patent protection in 1951. Sixty years later, silicon represented the next frontier for the legendary brand. It’s also worth mentioning that all of Patek Philippe’s applications in this field have been based on the traditional Swiss Lever Escapement compared to the more experimental approach favored by Ulysse Nardin.

Given its well-known preference for incremental updates, it’s no surprise that Rolex has been the most conservative of the trio. Starting in 2014, the world’s best-known luxury brand has used silicon escapements under the name of Syloxi in some of its ladies’ pieces to complement its well-established parachrom escapement.

The Swatch Group, on the other hand, has made the usage of silicon and other antimagnetic materials a defining part of its strategy in the 21st century. The biggest news in recent years, however, came in late 2018 when the Swatch Group announced its plan to equip all the watches produced by its 18 brands with either silicon hairsprings or the Nivachron hairspring (a recently developed alloy). While brands like Breguet, Omega and Blancpain have long incorporated silicon into their releases (some as early as 2006), other brands have been slower to catch on. A Swatch Group representative told WatchTime that it will likely take two to three years based on the volume of some of the brands within the group’s portfolio and that the decision to use either silicon or Nivachron is left up to the brands themselves. This is how we can see the new Tissot Gentleman lineup with a silicon escapement priced roughly at the same MSRP as the limited-edition Swatch Sistem51 Flymagic that features the first application of a Nivachron balance.

Richemont, owner of prestigious marques like Vacheron Constantin and Jaeger-LeCoultre, has made its own developments into the field of silicon that were made public with the introduction of the Twinspir balance in 2017 and the Baume & Mercier Clifton Baumatic range in 2018. Unfortunately, when the Baumatic returned to SIHH 2019 with a new perpetual calendar option as well as different color variants, its silicon escapement did not make it back. In the fall of 2018, the New Journal of Zürich reported that Richemont was being restricted in its usage of silicon due to patent claims by the Swatch Group, Rolex, and Patek Philippe-backed consortium.

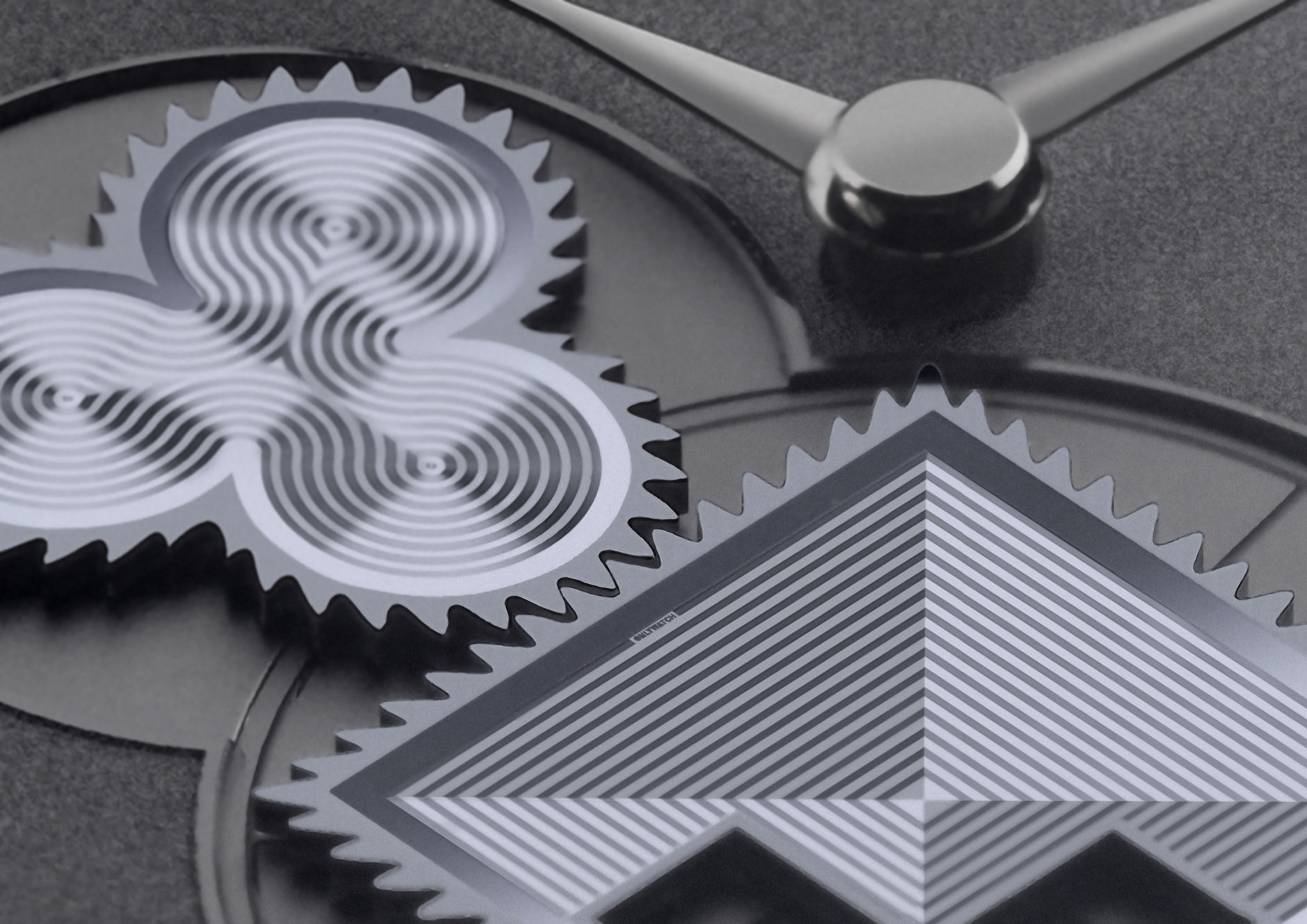

In 2017, Zenith made waves across the industry with the introduction of the Defy Lab, which featured a revolutionary new oscillator made from a wafer of silicon that is designed as a compliant mechanism and combines the functions of a balance, balance spring and lever in one single piece. Because of its silicon construction, it eliminated contact, friction, wear, slack, lubrication, assembly, and dispersions and, according to Zenith, offered an “almost 10 times higher” degree of accuracy with an average daily rate of 0.3 seconds. Memorably, the oscillator, which took up almost the entirety of the watch’s diameter, continuously vibrated, almost like a hummingbird. The Zenith Oscillator officially made its return earlier this year inside the new Defy Inventor line that was shown at Baselworld.

One of the other more memorable announcements that truly showcased the flexibility silicon allows watchmakers was the Girard-Perregaux Constant Escapement prototype from 2008 that featured a psychedelic-looking butterfly escapement design made of silicon set between the pallet and anchor wheels to keep the energy transmission consistent from the mainspring to the balance wheel. The Ulysse Nardin Anchor Escapement from 2014 used a similar concept but in much smaller dimensions. These designs would have been impossible to create with traditional materials.

Other smaller players have emerged as well. Maurice Lacroix focused on the elasticity of silicon when it introduced the unique piece Masterpiece Roue Carrée Seconde for the Only Watch auction in 2011 that featured silicon wheels in a variety of shapes that were visible from the watch’s dial. A production model called the Masterpiece Square Wheel was released in 2014. Frederique Constant jumped into the fray in 2014 with the FC-945 Silicium Heart Beat Caliber with an escape wheel, anchor, plateau, and parts of the gear train all made of silicon. At SIHH 2016, Parmigiani showcased the CSEM-developed Senfine Concept Watch with a special escapement utilizing silicon components to allow for a 70-day power reserve.

What You Need to Know Today

The two sides of the silicon debate basically fall on whether or not you believe in the continued pursuit of ultimate chronometric goals, or if you prefer the conservative ideology that has governed horology for decades. There is no right or wrong answer as both have their merits, but one thing is for sure: silicon and other high-tech materials are here to stay. This past January, TAG Heuer released an escapement built from a carbon composite that further pushes the realm of chronometric precision and reliability with plans to extend it into its collection from top to bottom. Looking into the early 2020s, it appears as if silicon is ready to gain even further market share as the patents held by the Rolex, Patek Philippe and the Swatch Group-backed CSEM consortium are set to expire in the coming years.

Continued horological innovation is an exciting prospect with large implications for the future viability of watch collecting regardless of how you feel as a collector and consumer. Although Ulysse Nardin fired the silicon starting gun close to two decades ago, it feels like only the first lap of the material’s application in watchmaking is coming to a close.

Silicon was just the starting point from copper, steel and brass. If you like the old technology, better grab it up while the watches are available. Soon silicon will be a thing of the past and carbon and other high tech materials will take over. That is the nature of progress. All materials have their advantages and disadvantages in collecting watches. I am beginning a collection of each type including quartz and wear them when the mood fits. Look on E-bay, used, for one owner bargains and enjoy.

As a watch lover of mechanical movements, it’s wonderful to learn about new materials.