1. The 9 Most Important Watches in the World

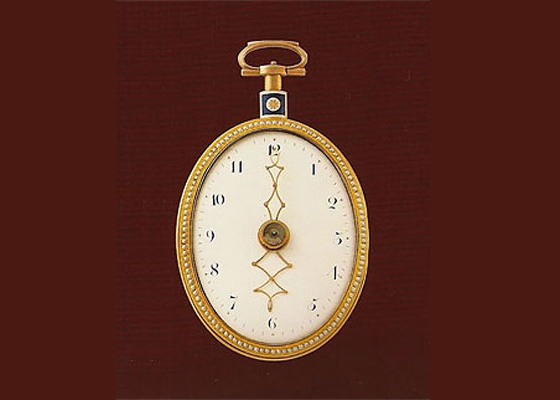

We just caught up with this interesting piece in Popular Mechanics written by John Biggs of crunchgear.com. Inside, Biggs takes a look at some pretty incredible mechanical watches from the past two centuries. For example, the watch below, from 1794, is called “The Pearl Star”, and is one of the earliest watches to utilize expanding hands. According to Biggs, “When the hands are at noon, they are fully extended up to the top of the case. When they are at 9:15, they automatically shorten to fit without touching the sides of the case.”

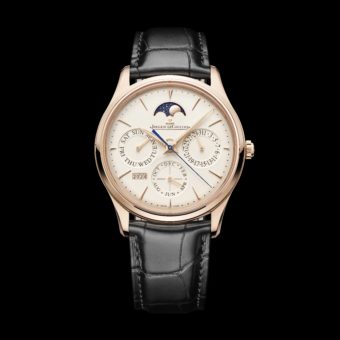

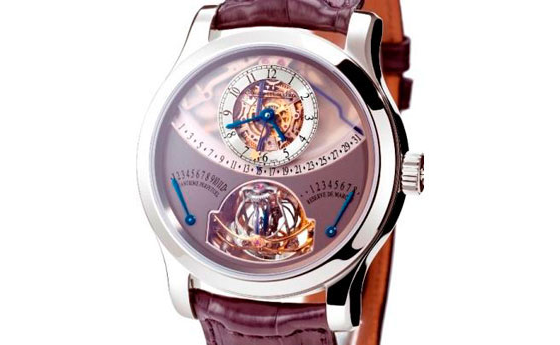

Jaeger-LeCoultre says that its 2006 Gyrotourbillon was the very first watch to leverage 21st-century technology to “perfect an invention created in the 18th century.” As the story is related, Abraham-Louis Breguet, the legendary French watchmaker (yes, he was born in Switzerland) invented the earliest tourbillons “in order to offset the effects of gravity on the balance wheel.” Jaeger-LeCoultre more recently sought to improve the mechanism and created the gyrotourbillon, a “three-dimensional wheel that rotates like a tiny planet on the watch face.”

For a more detailed description of the inner workings of the watch (both the original and the 2006 model) as well as to see all nine timepiece (and you really should see all nine timepieces!) you can read the original story right here.

2. What Time is It?

There was a time, not so long ago, when a person in a small town in the United States would ask the local barber for the time, and the barber might reply, “4:13.” At the exact moment, had that same person asked the saloon keeper for the correct time, the latter might have responded, “4:03.” Taking this just a little further, if the person went up to the town tailor, again at the very same moment, the tailor might have answered “4:08.” What gives?

The answer is to be found in a highly entertaining article in Wired.com (it’s from 2008, but timeless!).

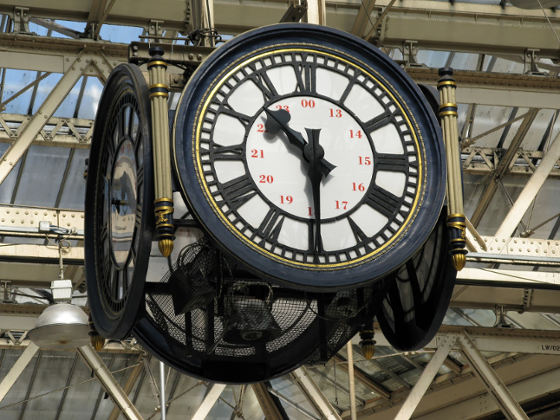

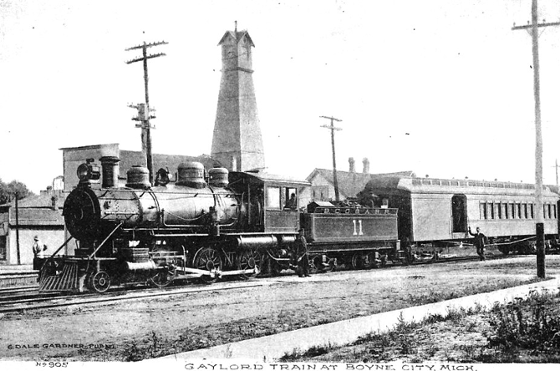

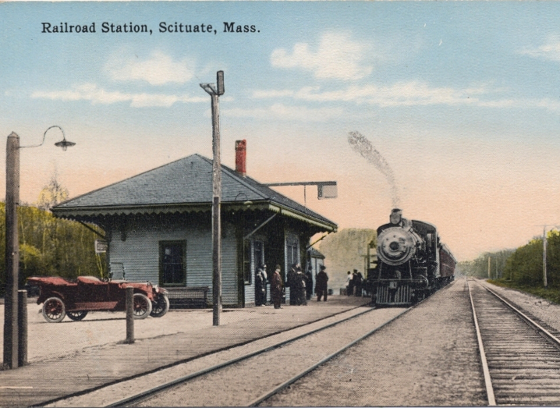

As detailed in the article, prior to November 18, 1883 — when the U.S. and Canadian railroads approved the use of five standard time zones to supersede an array of non-standardized local times in towns and cities across North America — nobody could be quite sure exactly what time it was. The new, standardized times came to be known as “railroad time.”

The British were ahead of the North Americans in this regard. They standardized their clocks according to Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) on Dec. 6, 1848. A movement to officially standardize time in the U.S. began in the 1870s, and the Congress finally enacted Standard Time on March 19, 1918, 35 years after the railroads initiated the project voluntarily.

Prior to standardization, timekeeping followed imprecise measures. Noon is when the sun is highest in the sky above, but depending on where your town was situated, noon might occur several minutes earlier or later than in other towns in your region. If a train was scheduled to arrive at noon according to the railroad timetable, you’d better have been sure you knew precisely when noon was.

For the railroads, adherence to timetables meant that paying passengers arrived on time and shippers were available to load their goods onto freight cars before the trains left. It was a matter of revenue.

We’ve only given you a taste of this story. You can read it in greater detail right here.