Starting the chronograph of the Zenith Defy El Primero by pressing the large rectangular pusher at 2 o’clock comes with a huge surprise: a long, thin hand spins around the dial at lightning speed. It only needs 1 second for each rotation. And inside the titanium case, the mechanism that makes this possible hums along at this high-speed pace, with an oscillating system that beats at a rate of 360,000 vph. This permits the measurement and display of 1/100-second intervals: 360,000 vph equals 100 beats per second, with as many steps by the hand in the same time interval.

The 1/100-second measurement is precisely displayed on the raised dial ring where it can be easily read. If the pusher at 2 o’clock is pressed again, the central chronograph hand stops immediately and shows the fractions of a second indicated by the elegant sword-shaped hand. Cleanly applied numerals in 10-digit increments mark 1/10 seconds, and intervening index lines show 1/100 seconds.

The full seconds time unit is displayed on a counter at 6 o’clock. So, for example, you can read 24 seconds, 7/10 of a second, and 3/100 of a second: 24.73. But by exposing the balance wheel, the otherwise easy-to-read lapsed seconds is interrupted by a concave section in the circle between seconds 40 to 52. If the elapsed seconds hand stops in this area, it’s harder to read the result because of the distorted line markers.

Due to the high frequency of the chronograph, the small elapsed seconds hand also appears to move at a rapid speed. In contrast, the elapsed minutes hand advances by one position each minute. This counter, at 3 o’clock, shows 30-time units in a conventional way. The power for the chronograph is sufficient for about 50 seconds if the wearer hasn’t wound the crown in the meantime. A fully wound barrel requires 25 turns of the crown.

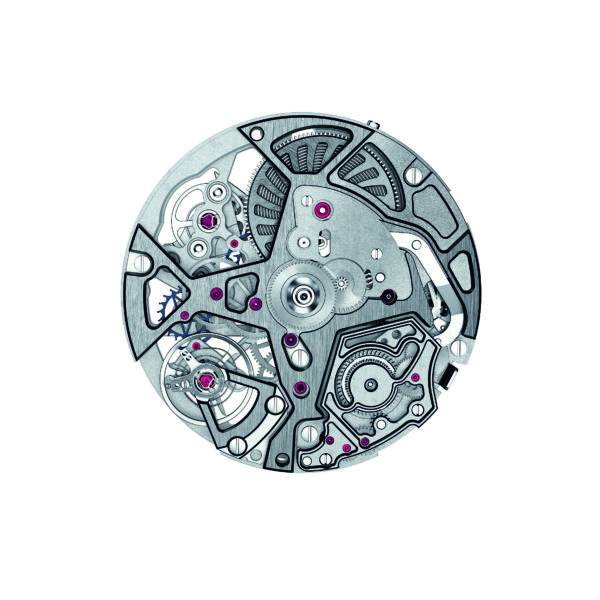

Behind this fascinating watch movement is a completely independent and separate chronograph mechanism that includes energy storage, a gear train, and a regulator. The second mechanism is linked to the El Primero 9004 by common plates and bridges.

Although the movement for the time display can be wound either by turning the crown counterclockwise by hand or automatically, by the motion of the rotor, the barrel for the chronograph mechanism can only be wound manually. There’s a very useful power-reserve display for the stopwatch function at 12 o’clock. Our test showed that a fully wound barrel provides almost 54 minutes (53:55.12) of timing capability. The watch movement has a power reserve of more than 50 hours and runs with a frequency of 36,000 vph, as befits an El Primero.

The separate mechanisms also make it possible to stop the watch movement while the chronograph continues to run. Whether you need this in daily use is another question, but the long-awaited hack mechanism in the El Primero movement is worth mentioning. Unfortunately, it’s out of place in our test watch, a skeletonized version of the Defy El Primero 21, because the small seconds with its three-piece propeller hand at 9 o’clock does not serve to set the time to the second. However, there is a version with a solid dial and a “normal” small seconds hand that allows for precise time setting. This model also has a stop seconds counter that is circular and easy to read.

Rate results were only determined using a timing machine: the fully wound watch lost just 0.4 seconds per day and gained about 2 seconds after 24 hours of running time (without rewinding). The watch is chronometer-certified according to COSC standards carried out by Timelab, the Foundation of the Laboratory of Horology and Engineering in Geneva. These rate results are achieved thanks to the separate mechanisms, in which the chronograph, when engaged, consumes no power from the watch movement, so its rate remains stable.

The El Primero 9004 consists of 203 individual parts, 75 fewer than the original El Primero, a compact solution using modern technology. It includes a patented chronograph design with a column wheel, an exclusive start mechanism and a patented reset mechanism with three heart cams. With the latter, all displays can be set to zero synchronously and accurately, a perfectly functioning process just like starting and stopping the chronograph.

Two innovative escapement systems include silicon components and carbon nanotube hairsprings, patented and manufactured by Zenith. According to Zenith, their physical and mechanical properties make them resistant to temperature fluctuations and the influences of magnetic shields far above the 15,000-gauss limit. We were not able to verify this limit in our test. Using a powerful horseshoe magnet, we applied 1,000 gauss and found that rate results were affected once the watch was within this magnetic field. The watch ran considerably faster but did not stop. Even the chronograph continued to run, with falling amplitudes. Once the watch was removed from the magnetic field, it returned to its previous rate after a period of time, but not if it was exposed to the magnetic field repeatedly. In this instance, it lost more than 20 seconds per day.

This result still remains within the scope of internationally accepted standards, which stipulate that a watch is anti-magnetic if it does not lose or gain more than 30 seconds per day. However, if we compare the Defy El Primero 21 with a certified Master Chronometer, it does not achieve the rate results needed for certification even at a much lower magnetic exposure than 15,000 gauss.

Zenith presents the El Primero inside a titanium case, using this material to represent the modern era while its design cites the long history of the manufacture. Back in 1880, Zenith founder Georges Favre-Jacot called his first machine-made pocketwatch the “Defi.” This striking timepiece was revisited in the late 1960s in a wristwatch collection known as “Defy.” (The change in spelling may have been made to appeal to an international market.) In line with the Defy philosophy of meeting a challenge, the watch was given a robust exterior – then as now – starting with a solid, oval mid-section that seamlessly transitions into short lugs, with brushed surfaces and polished beveled edges, and culminating in compact and perfectly clicking chronograph pushers, a robust and easy-to-use crown, and water resistance to 100 meters.

Despite its large size, the Defy sits comfortably on the wrist thanks to the compact shape of the case and the angled strap attachment. Unfortunately, the case doesn’t fit under a shirt cuff, and the single-sided, titanium folding clasp leaves pressure points, at the hinge on the wrist and at the high, sharp edge on the cuff side. Lateral pushers and a double prong for the leather and rubber strap provide some comfort and ease of use.

The skeletonized version of the Defy El Primero 21 with its greatly reduced dial shows the architecture, technology, and design of the El Primero 9004 caliber to its best effect. But it’s not for everyone, and Zenith also offers a more classic version with a solid, silver-colored dial. To our surprise, the skeletonized version we tested is easy to read, despite its numerous openings and perforations: the time is shown using faceted hands treated with luminous coating. And in the dark, even the hour markers around the edge of the dial glow brightly, ensuring that the time can be read easily.

The hands and markers follow the characteristic features of historical El Primero models, and the two circular tracks for the chronograph counters continue the historical thread using the colors blue and gray. The short end of the central chrono hand sports the Zenith star – a symbol for a turning point in the history of the brand, because never before has 1/100 of a second been measured with a Defy.

Great pleasure reading your article

To me the dial of a watch makes a major contribution to its look. Where is the dial in this case? Please Zenith.

A lot of information in this article is outdated. The carbon nanotube hairsprings were only on the prototype models, and did not make it into serial production – which would explain why your magnetism test showed the rate was affected.

Also, according to Zenith’s website, the serial production caliber 9004 has 293 components, not 203.

You also write in this article that the chrono function has a 50 second power reserve. I recognize this is a simple error, but where are the editors?