This article was originally published in the September/October 2022 Issue of the WatchTime print magazine.

A look back at the decade that saw an industry recover from crisis and steady itself at the cusp of a new millennium.

Jurassic Park is the biggest movie in the country, wide-legged jeans are everywhere and the masses are going crazy for Swatch. If you’ve somehow missed it: the nineties are back and people are obsessed with reliving the final decade of the analog era before digital technology completely took over. Somewhat ironically, the nineties were a time of revival and reinvigoration after the Quartz revolution nearly gutted the entire industry. The nineties ushered in a mechanical watchmaking renaissance through the embracing of rapidly developing computer-aided design (CAD) programs that sparked a high complication craze among brands like Patek Philippe and IWC, enabled the production of versatile high quality “everyday” movements from names like Zenith and Girard-Perregaux, and made the now-ubiquitous independent watchmaker a plausible reality.

The restoration wasn’t just Swiss. While this story would merit an article of its own, there was another watchmaking renaissance happening right across the border in the town of Glashütte, Germany. The proud tradition of German watchmaking dated back to 1845 but had been devastated by World War II and its aftermath. The late eighties and early nineties heralded a second coming for German watches, particularly three brands that are now practically ubiquitous for collectors: A. Lange & Söhne, Glashütte Original and Nomos Glashütte.

And then there are the cultural and societal changes over the course of the decade that empowered minds like Franck Muller and Jean-Claude Biver to revolutionize the way brands approach marketing. In a demure and conservative industry, these two saw the value of showing some swagger and brashness.

The early nineties saw watchmakers using technology as a tool that enabled horological innovation that would breathe new life into an industry that desperately needed to be rescued from the post-Quartz doldrums. This mechanical renaissance would have never happened were it not for digital tools like CAD programs that allowed previously impossible levels of precision and experimentation.

Trends are often reactions to what has come before and that certainly holds true here. In contrast to the ease, accuracy and affordability that propelled quartz movements to stratospheric if uninspiring heights, mechanical movements needed a more lavish display to recapture the hearts of collectors. And what better way to reignite the flame than with new and wonderfully dramatic complications? While it’s difficult to nail an exact starting point, the launch of the Patek Philippe Calibre 89 was a watershed moment in the mechanical renaissance of the nineties. Though technically launched in 1989 to coincide with the brand’s 150th anniversary, Patek Philippe’s 33-complication Calibre 89 was comprised of 1,728 parts and took nearly a decade from conception to completion. It was then the world’s most complicated watch and sold for a then-record $2.7 million at auction. It also wouldn’t have been possible without embracing technology.

Then-managing director Philippe Stern understood the coming necessity of utilizing and applying technological developments to traditional watchmaking. In a forward-thinking and prescient move, Stern and Patek Philippe Technical Director Max Studer hired a young engineer named Jean-Pierre Musy to spearhead development of the Calibre 89, which began nearly a decade prior in 1980. Back in that day it was highly unusual for Patek Philippe watchmakers to be working under an engineer. Still, armed with a keen understanding of micromechanics and some calculators (that app on your phone used to be a small brick-sized device, kids), Musy spent four years developing the Calibre 89.

Stern had invested $640,000 in CAD/CNC equipment, which paid off when the first Calibre 89 prototypes were created in 1984. After four more years of hard work and development, Patek Philippe master watchmaker Paul Buclin began work on assembling the final product. The rest is, as they say, history.

The Calibre 89 signaled the arrival of a slew of watches that were decidedly maximalist when it came to complications. In 1991, IWC released the world’s first grand complication watch followed by 1993’s Il Destriero Scafusia, which boasted a mind-boggling array of complications that included, but are not limited to, a split-seconds chronograph, perpetual calendar, minute repeater and tourbillon. IWC, Blancpain, Ulysse Nardin and of course Franck Muller, among others, kept the high-complication trend going through the decade.

Thankfully, the mechanical renaissance of the 1990s wasn’t restricted to these very upper echelons of watchmaking, which were out of reach for 99.9 percent of collectors. Access to CAD/CNC equipment allowed for drastic reduction of time in the concept phase as well as manufacturing the incredibly small and varied parts that go into watchmaking. Two excellent examples are the Girard-Perregaux Caliber 3100/3000 and Zenith’s slim Elite caliber. Reliable movements like the Elite were now capable of serving as base calibers for additional complications and would be in production for years to come.

The profile of independent watchmakers has seen a dramatic rise in the last few years. If you haven’t figured it out by now, the nineties were a seminal time in setting the stage for names like Philip Dufour, François-Paul Journe, Roger Dubuis, Michel Parmigiani, Daniel Roth and so many others. Just like with the larger brands developing new and better movements, it was computer technology that allowed these now-venerated names to turn their dreams into reality and make history.

Fortunately, there seem to be fewer snobs out there who drop their monocles and reach for the smelling salts at the mere mention of computers or machines during a conversation about watchmaking. The romantic image of a watchmaker hunched over his table using only the same tools as his ancestors is a nice one but an absolute fiction. The reality is that it was only when CAD/CNC technology became available to this generation of nowlegendary watchmakers that they felt equipped and prepared to go out on their own. For example, Dufour taught himself how to use CAD software, telling Europa Star in 2000, “This was a great discovery. It allowed me to go further and faster, to memorize data, to create designs and to ensure the indispensable consistency in my operations.”

Dufour’s inaugural watch was a Grande Sonnerie (of course Dufour starts with this remarkably complex complication) that was a hit at the 1992 International Watch, Clock and Jewellery Fair at Basel. The attention and success resulted in several sales and validated Dufour’s decision to dedicate himself to his own brand.

There is one independent watchmaker whose breadth and scope of influence during the 1990s and beyond is woefully underappreciated — and I’d venture to say even callously derided — these days: Franck Muller. Long known as the “Master of Complications,” Muller may be one of the most interesting, accomplished and ultimately misunderstood watchmakers of not just the nineties but the last 40 years. There are several explanations as to why public opinion turned as drastically as it did, though an approaching obsession with “minimalism” the last decade or two would partially explain a lingering hostility to the loud uninhibited designs that carried Muller to fame.

Though he had been producing his own highly complicated watches for some years, the Franck Muller brand was officially founded in 1991. This was a particularly pioneering move at the time because, unlike today, highly gifted watchmakers overwhelmingly preferred to safely stay behind the scenes at the larger brands. And understandably so. After all, how could even the most gifted and creative independent watchmaker go out and create a brand that would appeal to collectors when the established names had dominated the industry for over a century?

Muller was undeterred and partnered up with casemaker Vartan Sirmakes to create his eponymous brand in the early nineties. Initially riding the high complication wave, Muller quickly became known for creations built around the tourbillon, earning him the moniker “Master of Complications.” Franck Muller was everywhere in the nineties, bringing flash and showiness to a staid industry.

In the early aughts, Franck Muller the man and Franck Muller the brand parted ways after some welldocumented public issues. Though the influence of Franck Muller on today’s watch industry is undeniable, his legacy has not yet been cemented and is long overdue for a correction.

Now, the other great watch personality from the nineties certainly enjoys his share of adoration from both the industry and enthusiast community as well as from more casual mainstream observers. Of course, I’m talking about Jean-Claude Biver, the marketing mind behind the great revivals of Blancpain, Omega, and later on, Hublot. For the purpose of looking at how the nineties influenced today’s watch market and community, it is the Omega turnaround that exemplifies Biver.

Omega had been a sleeping giant for decades leading up to Biver’s taking the helm in 1993. Of course, rousing a sleeping giant is easier said than done and it’s not exactly fair to give total credit to the charismatic marketing maven. In the years leading up to Biver’s takeover, Omega had recognized the folly of prioritizing high production while neglecting proper marketing in the wake of the Quartz revolution. By the time Biver arrived, Omega had cut product lines down from seven to four with flagship models cut from 35 down to 12 and, remarkably, just between 1986 and 1988, references went down from 2,000 to 500.

Discarding lower tier models and abandoning lowpriced methods like gold-plating allowed Biver to reframe the brand in a higher tier by actually delivering higher quality products. But the brand’s success couldn’t rely on product quality alone, especially when considering Omega’s marketing prowess in the past.

Being the watch worn by astronauts during the first moon landing and being a major sponsor of the Olympics were two huge marketing coups but there had not been anything new in the same vein for decades by the time Biver was in charge. It was sometime in the early or midnineties when it was suggested to Biver that they should try and get an Omega on the wrist of agent 007 in the upcoming James Bond movie. The Bond franchise had been dormant for years with the previous release being 1989’s License to Kill, which was Timothy Dalton’s second and final film playing 007. Now with Pierce Brosnan freshly cast in the role, Bond was due for a comeback. Even so, Biver was initially resistant to the idea of a partnership. These days it would be unfathomable to pass it up but the franchise really had lost much of its luster and Biver worried it would make Omega look past its prime.

Of course, eventually he acquiesced, which would prove to be one of the savviest marketing decisions in his career. GoldenEye was a hit and Pierce Brosnan made the Seamaster 300M the coolest watch around. And though it came out a couple of years later in 1997, the watch was featured prominently in the Nintendo 64 video game tie-in, which sold over eight million units and captivated a whole new generation of future 007 fans like myself. Crossover marketing at this scale had really never been done before in the watch industry, which is almost unbelievable in 2022.

Everyone wanted the Bond watch and sales soared. Omega’s partnership with 007 continues to this day and remains the gold standard of watch placement in Hollywood or any media.

Of course, it wouldn’t be a discussion about the nineties without getting into the trends of the time. As much as I’d love to write an exegesis on JNCO jeans and the graveyard of forgotten Tamagotchis left in the wake of that decade, I will focus on the watches for now. At this point it’s a bit obvious to point out how “big” watches like Panerai and the Royal Oak Offshore were all that and a bag of chips at the time. There is, however, another trend that began to get traction in the nineties and has now grown into one of the biggest segments of the luxury watch market.

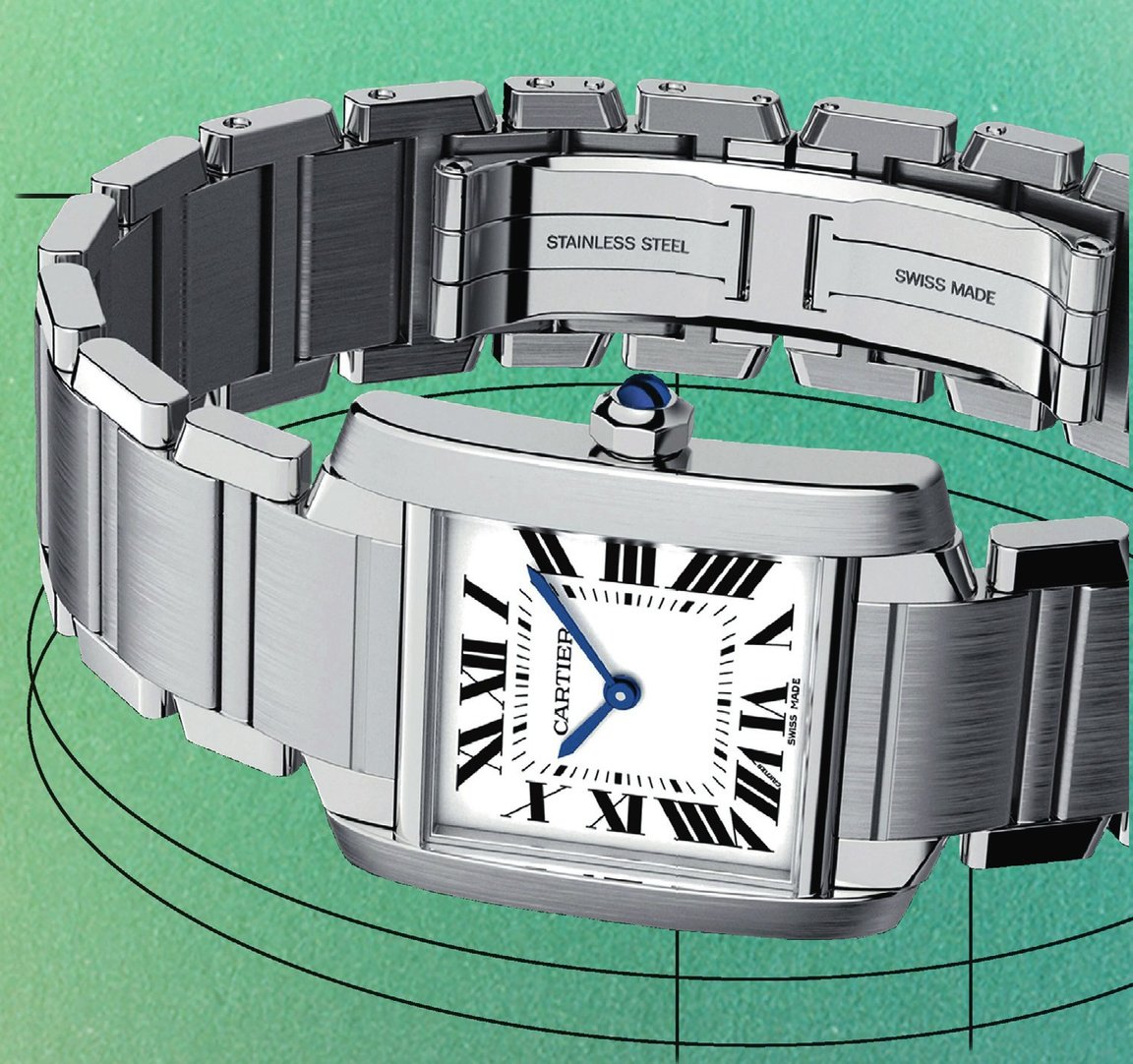

Landing outside the woefully tired and insufficiently broad designations of “sport” or “dress” watch came pieces like the Patek Philippe Aquanaut in 1997, the Vacheron Constantin Oversears in 1996, and, I would argue, the Cartier Tank Française, also in 1996. These “leisure” luxury watches reflected the wishes of a younger collector whose lifestyle isn’t quite so rigidly regimented. Remember, this is before the richest people in the world wore t-shirts and flip-flops, but the signs of weariness with the old-fashioned way of doing things was clear.

These days just about every bran has a luxury sports watch but other than the Patek Philippe Nautilus and Audemars Piguet Royal Oak, there weren’t many options back in the nineties. An Aquanaut or Overseas fit in at the office, formal occasions, weekend activities, really just about anything. An unintentionally positive and forward-looking development is just how appealing to women these leisurely luxury watches were. The Aquanaut was, likely by default, intended as a men’s watch but in its first year of release a staggering 50 percent of buyers were women who purchased it for themselves. These watches went against the “big watch” trend of the time and stuck to sub-40mm cases, a move that would both pay off and age well.

The Aquanaut and Overseas have been written about and fawned over exhaustively by now, and rightfully so. An absolute sales smash from its launch in 1996 to this day, the Cartier Tank Française still doesn’t always get its due, especially from enthusiasts. The Tank Française was a success because it retained all the classic iconic elements of the Cartier Tank but coupled them with some fresher contemporary elements like an angular case and brancards. And then there was the new integrated bracelet that pulled the whole thing together. Turns out putting a fresh-looking new Cartier watch on what is ostensibly a piece of Cartier jewelry with a bracelet was a recipe for a hit.

According to Vanity Fair, a then recently-divorced Princess Diana ditched her engraved Patek Philippe that was gifted to her by Prince Charles for a Tank Française that she would wear all the time both “for formal and casual engagements.” And that, again, highlights why pieces like this got so popular: offering versatility and refinement without stuffiness. Times were indeed changing.

During the latter part of the nineties, we saw the consolidation of an increasing number of brand’s under the umbrella of either Swatch, Richemont, or then-newcomer the LVMH group. Time has only reinforced that this was the way things were heading as about half of all the Swiss watch sales in 2021 were by one of these luxury conglomerates.

The nineties can be seen as a transitional time for the watch world, sandwiched between the Quartz revolution and the digital revolution. One thing is for certain, it was the pioneering vision of a handful of people that propelled the industry from the doldrums into the new millennium.

To subscribe to the WatchTime print magazine, click here.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this article, particularly the numerous historic references made to the various brands. However the article’s focus on the mechanical watch industry’s “restoration wasn’t just Swiss” story failed to mention that the 90’s also spawned the resurgence of independent watchmakers in the U.S., led by the incomparable Roland G Murphy of RGM.

Although Roland and Franck Mueller launched their respective brands at almost the same time, it’s interesting to note that RGM today continues to prosper under Murphy’s personal direction, while the latest Muller watches merely carry its founder’s name.

I’m glad they mentioned the Bond Seamaster as one of the great designs of the decade and really created many a watch fan. IWC also had a great lineup and introduced many complications at accessible price points, like their pilot’s watch doppelchronograph and GST line with mechanical alarm, split seconds and perpetual calendar watches.