In modern watchmaking, many complications that were once difficult to produce (and therefore very expensive) have become gradually less and less so. Watch brands, driven by a desire to offer better value to consumers (and more pressure to do so, as the buying boom of the early 2000s levels off) are more and more taking advantage of industrial fabrication methods to make complications like tourbillons and perpetual calendars more affordable than ever before. But there are still a few complications that resist this trend – and one of them is the minute repeater.

Rather than becoming more and more affordable, almost the opposite trend can be seen in repeaters – they are becoming, increasingly, places where brands showcase their highest expertise, and at correspondingly high prices as well. One of the most recent watches to fall into this category is Audemars Piguet’s “Supersonnerie” — a minute repeater eight years in the making, intended to offer a slew of technical improvements that AP thinks will make it nothing less than the best-sounding repeater in the world. (The term “sonnerie” is most often seen in reference to grande sonnerie watches, which strike the time in passing rather than on demand; however, the term taken alone may also refer to a repeater, which strikes on demand. The use of “sonnerie” here might be confusing, so we should clarify that the Supersonnerie is a minute repeater, rather than a grande sonnerie.)

To understand why, it helps to look at what a minute repeater is, and how it does what it does.

A minute repeater is a watch that chimes the time “on demand” — that is, it rings the time when you tell it to. Typically, a repeater springs into action when you push a slide set into the side of the case. Pushing the slide winds a spring that powers the chiming operation. A classic minute repeater will ring on two gongs: one lower in pitch, and one higher. The hours ring on the lower pitched gong. The number of quarter hours past the hour are indicated by a chime on both the lower and higher gong. And the minutes chime on the higher gong.

Inside every minute repeater is a complicated system of gears, cams, and levers making up the minute repeater complication. The minute repeater complication basically works by reading the time mechanically from the position of the hands and then chiming the time. The minute repeater is not a new complication at all; it existed in basically its modern form by the time of Breguet.

Abraham-Louis Breguet was also fascinated from very early on by repeating watches. In 1783 he created the first striking repeating watch to be operated by a gong rather than a bell, which had been universally used until then. Initially straight, and mounted crosswise on the back plate, the gong evolved to a circular form, coiled around the movement. It had the advantage of dramatically reducing the thickness of striking watches, while at the same time making the tone more harmonious and clearer. An exceptionally useful invention, it was adopted immediately by most contemporary watchmakers. Breguet also invented multiple striking mechanisms for repeating watches, notably for the quarters, half-quarters and minutes. Just as in Breguet’s time, modern watchmakers face certain challenges: making the repeater as loud as possible but at the same time making it sound pleasant. Also, repeaters can chime the time at different tempos, depending on how the repeater is adjusted, and a watch that chimes too fast or too slow may sound unpleasant. Perhaps more than any other complication, a minute repeater requires the watchmaker to understand the watch as a whole, as the quality of sound is intimately related to the construction of the case and dial as well.

The Supersonnerie began with the idea of taking all the basic parts of a repeater – the striking system, case, regulating system, and so on — and seeing what could be done to improve them as much as possible. The project was spearheaded by Giulio Papi, and Audemars Piguet Renaud et Papi (APRP). APRP was founded in 1986, by Dominique Renaud (who has since left the company) and Giulio Papi, as Renaud & Papi, and, over the years, some of the most famous names in modern horology have worked there, including Stephen Forsey of Greubel Forsey and Cartier’s head of fine watchmaking, Carole Forestier. The company eventually became part of Audemars Piguet, which now has 80 percent ownership, and APRP has been known for many years as one of the top complications specialists in the world. That a research program was in place first became apparent to the general public when the Acoustic Research RD 1 concept watch was shown at the SIHH in 2015 – the watch could be heard, and the sound was remarkable, but Audemars Piguet gave few details as to the actual specifics of the development process. With the debut of the Supersonnerie, however, the steps taken in that research can now be discussed in more detail.

The first step was to analyze the sound created by a repeater, in order to have a solid, objective basis for changes and improvements. Traditionally repeaters were tuned, and had their sound refined, by ear. Today, however, finding a watchmaker with the necessary sense of musical tone is difficult (near impossible, Giulio Papi said, at a discussion at APRP) and so, having a sound profile of the optimum sound characteristics was a necessary way to begin.

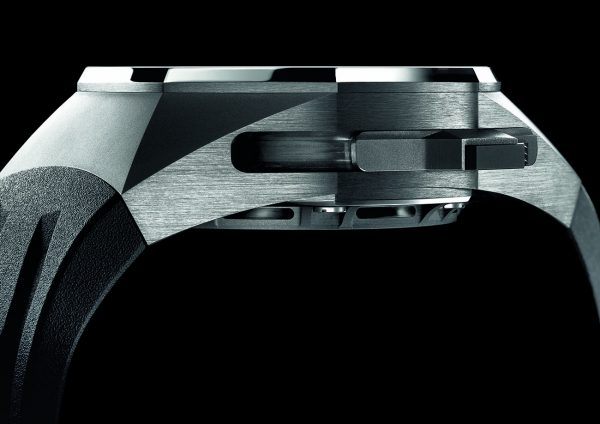

The sound recordings took place in a special chamber designed to eliminate confusing echoes, and for the analysis, APRP was assisted by the École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Lausanne), which has a long history of providing technical assistance and microengineering expertise to watch brands. Eventually, a sound profile was created that allowed the first hurdle to be overcome: creating a way of making the gongs that were already close to the ideal sound character. The circular, hardened steel gongs of a repeater can be tuned in two basic ways: by reducing their overall length (which heightens the pitch) or by filling the base of the gong where it is attached to a small steel block. The ability to make a gong with certain ideal sound properties yielded the first patent associated with the Supersonnerie project. The second problem was that of sound transmission. Minute repeaters traditionally were not waterproof or dustproof. As the repeater is a delicate mechanism, repeating watches have never been sports watches, and also, a heavy, durable, waterproof watch case tends to muffle sound volume as well as deaden tone. The best-sounding traditional repeating watches, therefore, tended to have no gaskets and to have relatively thin cases (the best sound was thought to come from rose gold). The Supersonnerie, however, is designed for 20-meter water resistance and has a titanium case.

The solution to the problem of how to get good tone and volume out of a water-resistant watch was solved by changing how the gongs are mounted in the watch. Normally in a repeater, the block for the gongs is screwed onto the movement plate, on the side of the movement opposite the dial (in repeaters with display backs, the only part of the chiming system that is visible is usually the regulator, the hammers, and the gongs themselves). This means the sound has to travel through the caseback, and that the dial, crystal, and case act as resonating surfaces. The combination of all these factors is what determines the final sound.

In the Supersonnerie, the gongs aren’t attached to the movement plate. Instead, they are attached to a “soundboard” — a membrane made of titanium, which covers the back of the movement. This membrane is held in place by screws and forms a water-tight seal. When the chimes are struck, the membrane acts like the soundboard of a string instrument like a guitar or violin. It has been designed so that its natural frequency closely matches that of the chimes, and it dramatically amplifies the sound of the chimes as well as giving them a clear, pleasing sound. The actual caseback covers the thin, relatively delicate membrane and has apertures along its edge to allow sound to escape. Interestingly, the system works so well that the watch actually sounds louder, with a better tone, when the watch is strapped on the wrist.

The third basic problem in repeaters is that you have to have some way of controlling how fast the gongs are struck — that is, you have to control the tempo. There are several different ways of doing this. Traditionally, watchmakers used an anchor, similar to the anchor escapement. The system works well and it is very reliable, but it also produces a distinct buzzing noise. Another solution is the so-called “fly” regulator. In this system, a rotor attached to the chiming gear train spins as the chimes are struck. As it turns, centrifugal force causes two arms to extend, which make contact with the walls of the rotor housing. The friction created slows the speed of chiming. The system makes a lot less noise than the anchor system, but the speed of chiming can vary over time thanks to deterioration of the oils used to lubricate the rotor. Also, the system is much harder to adjust than the anchor system. For that reason, and also because of its long use of its own legacy designs (AP is one of the very few companies that didn’t stop making repeaters during the quartz crisis), Audemars Piguet has generally used the anchor system.

However, the team at APRP did find something interesting: most of the noise in the anchor system isn’t made by the anchor itself. Instead, a lot of it actually comes from the vibration of the pivot on which it’s mounted. Therefore, a new anchor was designed, which has a flexible structure that actually absorbs most of the vibration force before it can be transmitted to the anchor’s pivots. The smallest part of the new anchor is extremely thin — only 0.08 mm, and the whole thing is only 1.5 mm overall.

And, there is yet another feature with which the Supersonnerie improves on conventional repeaters. In most minute repeaters, the sequence of chiming is hours first, then quarter hours (up to three) and then, finally, the minutes. However, if no quarters are to be struck, there is a period of silence as the gear train passes over the interval where the quarters would be. This sound gap interrupts the continuity of the chimes. APRP has actually developed a new construction for the chiming system that eliminates this gap.

The result is a watch that has a truly unique combination of volume, sound quality, and absence of distractions like interruptions to the strike, or the sound of a regulator. It’s a truly incredible experience to hear it, as we were lucky enough to do recently at APRP in Le Locle. We were given the opportunity to hear many vintage AP repeaters as well, which all had wonderful sound but which, as they grow smaller, struggle to make themselves heard; as well, of course, they are not waterproof and are generally very fragile.

In the Supersonnerie, we have a really modern repeater — one with sound that can easily be heard and appreciated even with a lot of background noise. There are three patents granted — one for the sound board membrane system, one for the system of manufacturing the gongs, and one for the tiny, virtually inaudible regulator. We were informed that the advances made for the Supersonnerie will also find their way into future repeaters — which means that, thanks to Audemars Piguet Renaud & Papi, we can look forward to a whole new generation of sound.

SPECS:

Manufacturer: Audemars Piguet & Cie SA Manufacture d’horlogerie, route de France 16, 1348 Le Brassus/VD, Switzerland

Reference number: 26577TI.OO.D002CA.01

Functions: Minute repeater on two gongs, tourbillon, chronograph with sweep-seconds hand, 30-minute counter, hours, minutes

Movement: Hand-wound manufacture Caliber 2937 consisting of 478 parts, 21,600 vph, 43 jewels, 42-hour power reserve, diameter = 29.90 mm, height = 8.28 mm

Case: Titanium, sapphire crystal, titanium bezel, black ceramic screw-in crown, black ceramic and titanium push-pieces, titanium push-piece guards, water resistant to 20 meters

Strap and clasp: Black rubber strap with titanium folding clasp

Dimensions: Diameter = 44 mm, height = 16.5 mm

WOW! It just amazes me how all the intricate internals of the movement of a fine made watch all come together and the watchmakers who design and make these watches. I have to give a huge applause to this watch. One day I know it will be on my wrist! OUTSTANDING!

I didn’t notice that you mentioned the price or did I just miss it – how much?